The Banco de Materiais is helping keep alive Porto’s heritage of Azulejo tiles.

Azulejo Tile origin story

Azulejos are painted glazed ceramic tiles. They’re traditionally blue and white, though they can be painted any color.

The earliest version of the tiles first came to the Iberian peninsula in the 13th century CE during Muslim rule. These tiles were more like mosaics, glazed and cut and then reassembled into geometric patterns. Mudéjar artisans continued making Azulejos after the Reconquista by the Christians.

When Portuguese King Manuel I visited Seville in 1503, he became enamored with the style and soon royal palace walls in Portugal were covered with Azulejo.

Azulejos in Porto

Amazing Azulejo murals and tilework are found all over Portugal. Artisans continue practicing the form and taking it to new heights with modern interpretations.

While the National Tile Museum is in Lisbon, Porto is home to countless amazing works of Azulejo.

The most famous is the São Bento railway station with several striking murals depicting notable scenes in Portuguese history as well as images of Portugal’s rural past. Artist Jorge Colaço took 11 years to complete the massive project which debuted in 1916.

Religious Azulejo works are inside many churches in Porto but some of the most impressive cover church’s exterior walls like the massive murals on the Chapel of the Souls.

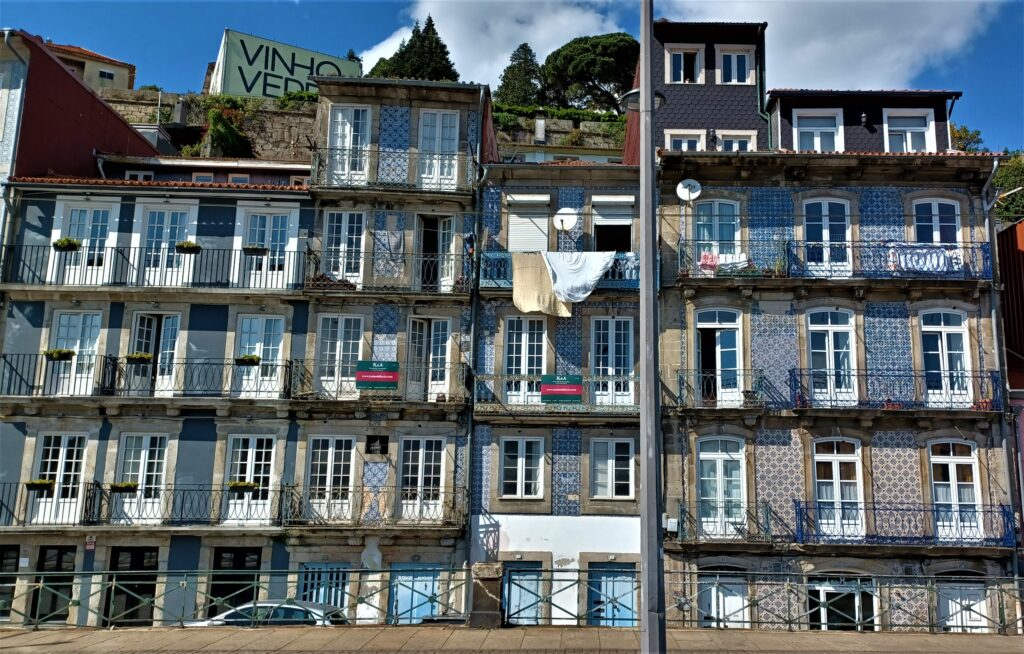

There are also everyday examples of Azulejo work covering the facades and interiors of commercial and residential buildings all over Porto. And it’s this architectural heritage that the city is trying to preserve. That’s where the Banco de Materiais comes in.

Banco de Materiais

Set up as a depository for tiles, the space is more of a warehouse with rows and rows of shelves filled with hundreds of boxes of Azulejo, each numbered and inventoried.

So, where do the tiles come from?

One source is builders and developers who bring the tiles to the bank for safekeeping. But, they’re not the only ones. Law enforcement brings tiles that are seized from criminals. The fire department collects tiles from buildings that are in danger of collapse.

When a builder or developer is renovating or restoring a building they can come to the Banco de Materiais and take tiles for free, but only if they match the color, pattern, and format of the existing work.

The Banco de Materiais is free to enter and browse, just don’t touch any of the tiles or you will be scolded. I know, we were.

Banco de Materiais in action

Because so much building and restoration has been done in Porto in the last 15 years, tens of thousands of tiles have been given to builders.

We were wandering around downtown Porto on our last trip there and I saw a couple of workers in vests and hardhats pointing at tiles on the façade of building. They took pictures and scribbled notes in a book.

I asked them what they were doing. They told me they worked for the Metro (subway) which was doing some construction nearby. One of the women said that they were inspecting all the buildings near the construction site for damage to the Azulejos. With so much pounding and hammering, the vibrations from the construction work could cause the tiles to crack or the mortar to fail, allowing the tiles to fall and smash on the concrete sidewalk, potentially injuring someone.

“If you find damage, would the tile be replaced by one at the Banco de Materiais?” I asked. The worker smiled, obviously happy that I was aware of the bank. “Yes, we would do that,” she replied.

About the Author

Brent Petersen is the Editor-in-Chief of Destination Eat Drink. He currently resides in Setubal, Portugal. Brent has written the novel “Truffle Hunt” (Eckhartz Press) and the short story collection “That Bird.” He’s also written dozens of foodie travel guides to cities around the world on Destination Eat Drink, including in-depth eating and drinking guides to Lisbon, Porto , Sintra, Monsaraz, and Batalha in Portugal. Brent’s podcast, also called Destination Eat Drink, is available on all major podcasting platforms and is distributed by the Radio Misfits Podcast Network.