These secret passageways have helped merchants move their goods and hide the resistance fighters who took on the Nazis in WWII.

Traboules origin story

Lyon was originally settled in the first century BCE as a Roman town. By the 4th century CE, Lyon had been built up, but with a poor plan of long streets parallel to the river.

As there were few crossroads, it was difficult to get to the river for fresh water and transportation without taking a long detour.

So, little passageways were built to gain access to the river. Unlike alleyways, the new passageways, called Traboules, were covered.

The Traboules also commonly featured distinctive architectural elements like curved archways, spiral staircases, and pastel colors.

The Canuts

In the 19th century, silk manufacturing was the largest industry in Lyon. Half the population was employed in the silk trade or economically dependent on it.

The weavers (Canuts) acted as independent contractors, being paid a fixed price per piece. The Canuts employed various apprentices and women who prepared the silk for the looms. Workers also were employed to repair the looms.

As the finished textiles were a delicate product, it was important to keep the silk safe and out of the elements when transporting it to the river where boats shipped the fancy fabric to wealthy customers around the world.

When the worldwide economy was good, so was life for the Canuts (though not quite as good for their apprentices and women laborers). But, when the economy crashed, like in the Panic of 1825, no one wanted to buy a luxury item like silk.

Wages were slashed and the Canuts protested. They tried to set minimum prices, but to no avail.

In 1831, conditions for silk workers had deteriorated to such a point that violent protests broke out. The slogan “Vivre libre en travaillant ou mourir en combattant!” (Live free working or die fighting!) was shouted by protesters. Workers captured a police barracks and took weapons from the arsenal. Many National Guardsmen, whose dayjobs were as Canuts, changed sides and began fighting with the protesters, eventually taking over City Hall.

The government in Paris sent 20,000 troops to Lyon to quell the violence, but by the time they arrived, the fighting was over and they regained control of the city without further bloodshed.

But, this was not an end to the silk workers movement. There were violent revolts in 1834 and 1848, both resulting in much loss of life.

Resistance Fighters

During WWII, Lyon was occupied by the Nazis. But, Lyon was also a base for the French Resistance.

French fighters used guerilla tactics to kill German soldiers and destroy their supplies. Resistance soldiers used Traboules to hold secret meetings since they were relatively easy to keep lookout and had multiple escape routes if they were discovered. Traboules also made handy spots to disappear into once a military mission was carried out.

Jean Moulin was the President of the National Council of the Resistance and one of the most prominent French freedom fighters. On June 21st, 1943, Moulin, along with other members of the Resistance, was arrested at a house outside Lyon. He was tortured by the infamous “Butcher of Lyon” Klaus Barbie. Moulin died shortly thereafter.

Barbie, head of the Gestapo in Lyon, took perverse delight in personally torturing many prisoners. He is thought to be directly responsible for 14,000 deaths.

After the war, Barbie worked for the U.S. Army in their anti-Communist Counterintelligence Corps. When the French discovered this, they demanded Barbie be handed over, as he had been sentenced to death in absentia by a French court. The U.S. refused and Barbie fled to Bolivia and lived freely under the alias Klaus Altman. There, under multiple Bolivian dictators, he trained military personnel in interrogation and torture methods as well as assisting in the illegal arrest and murder of political opponents.

Barbie also worked with drug cartels in South America, including the notorious Pablo Escobar, selling them weapons and providing protection to their drug supplies.

Nazi hunters uncovered Barbie’s identity in 1971, but he wasn’t extradited until 1983 when democracy returned to Bolivia. He was tried and found guilty in 1987. Klaus Barbie died in prison 4 years later.

Today, the building that Barbie used as his headquarters in Lyon and where he personally tortured prisoners is a museum dedicated chronicling the Resistance and Deportation of Jews in WWII.

Visiting Traboules

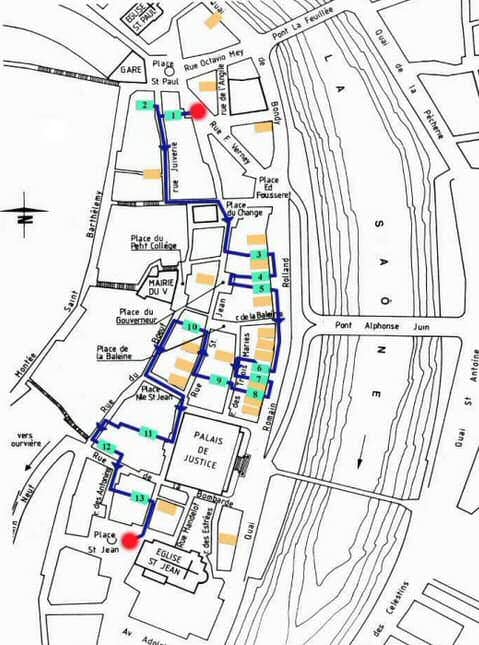

There are over 400 Traboules in Lyon. But, only about 40 are open to the public.

The longest Traboule connects 54 Rue Saint-Jean to 27 Rue du Boeuf. One of the most beautiful traboule connects 9 Place Colbert to14 bis montee Saint Sebastion. It features a six story external staircase.

If you want to see several traboules, download this map. Entrances to the Traboules are often marked with a bronze shield. Or you can take the Free Tour Lyon, which visits a couple Traboules. Remember that the free tour isn’t really free; you should always tip your guide.

Keep in mind that when you visit a traboule you are visiting someone’s neighborhood. Traboules, while open to the public, are like courtyards in apartment buildings. Families live here so keep your voices low and refrain from taking pictures of people without their permission. Think of how you would feel if someone took a picture of you through the window of your house.

About the Author

Brent Petersen is the Editor-in-Chief of Destination Eat Drink. He currently resides in Setubal, Portugal. Brent has written the novel “Truffle Hunt” (Eckhartz Press) and the short story collection “That Bird.” He’s also written dozens of foodie travel guides to cities around the world on Destination Eat Drink, including in-depth eating and drinking guides to Lisbon, Porto, Sintra, Monsaraz, and Evora in Portugal. Brent’s podcast, also called Destination Eat Drink, is available on all major podcasting platforms and is distributed by the Radio Misfits Podcast Network.